You know the Eames lounge chair. Maybe you’ve seen Powers of Ten. But did you know Charles and Ray Eames thought a lot about toys like kites and spinning tops?

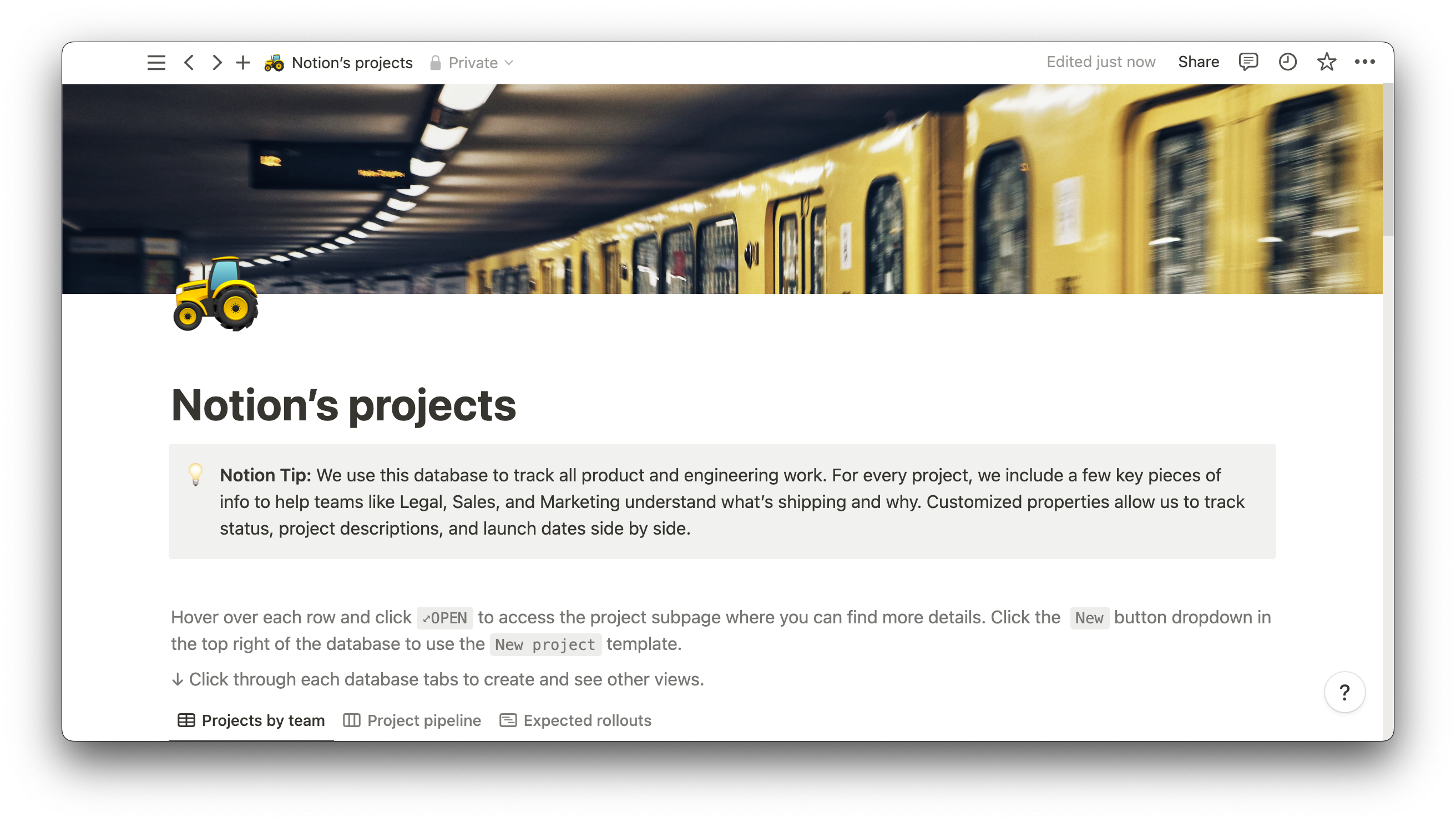

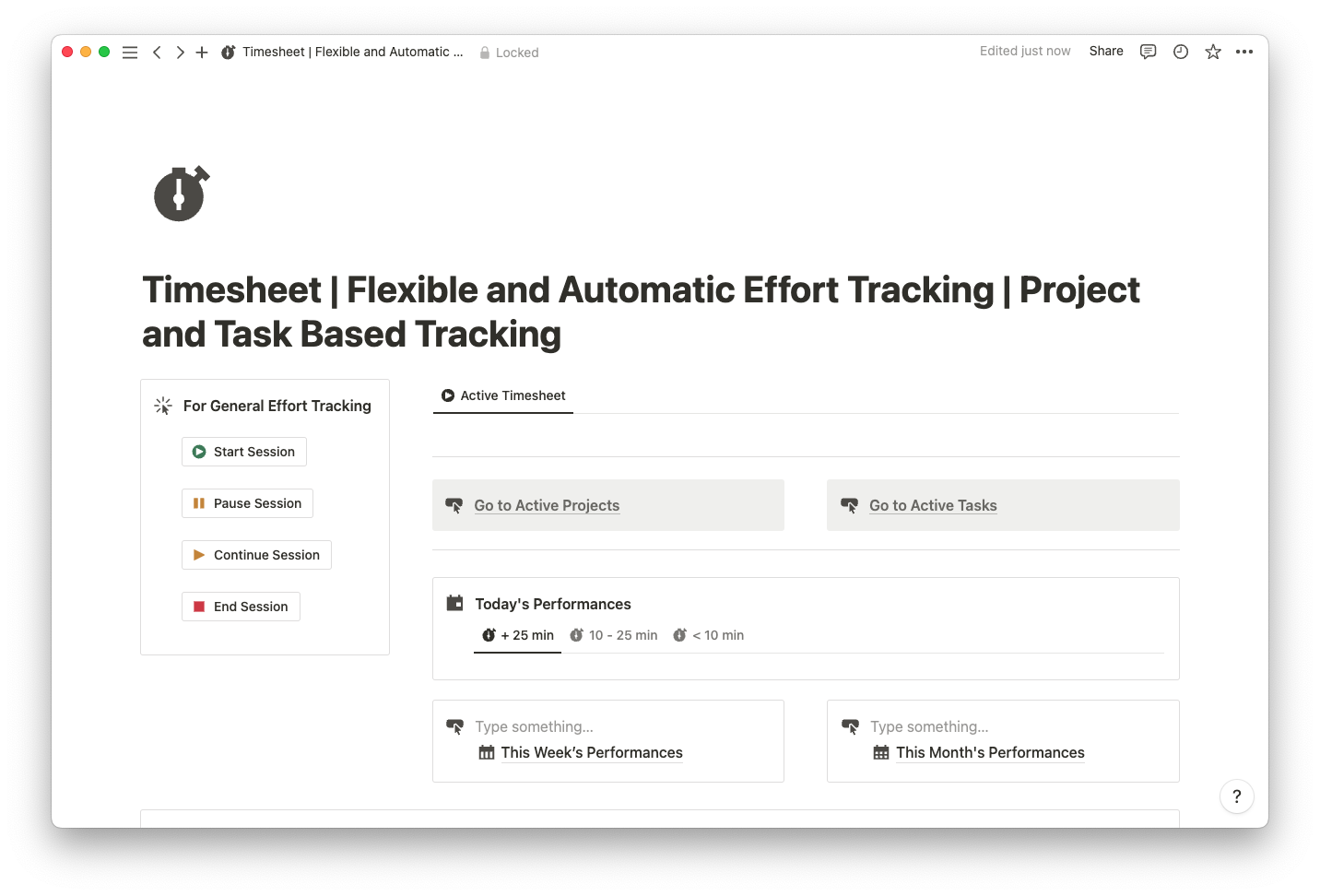

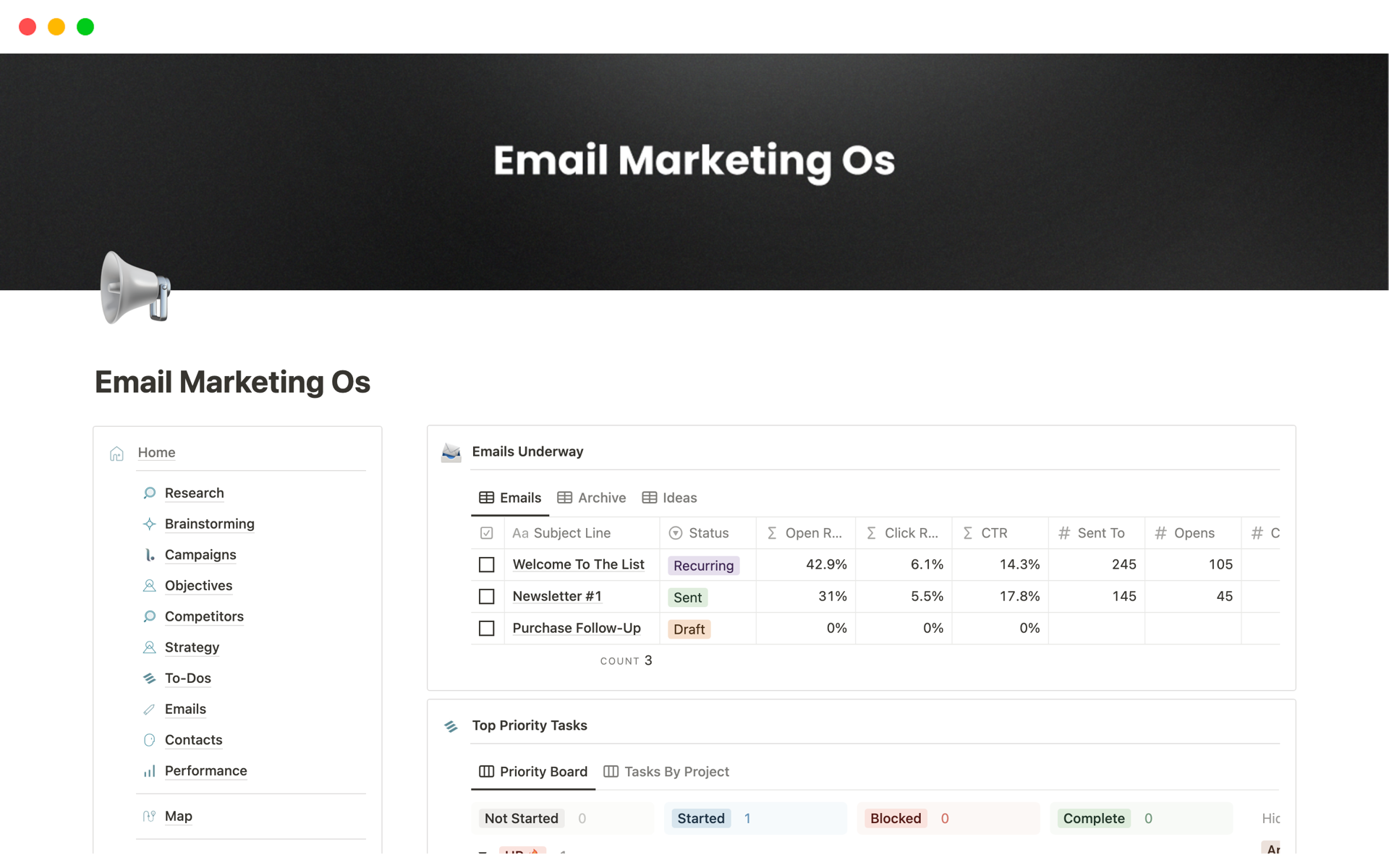

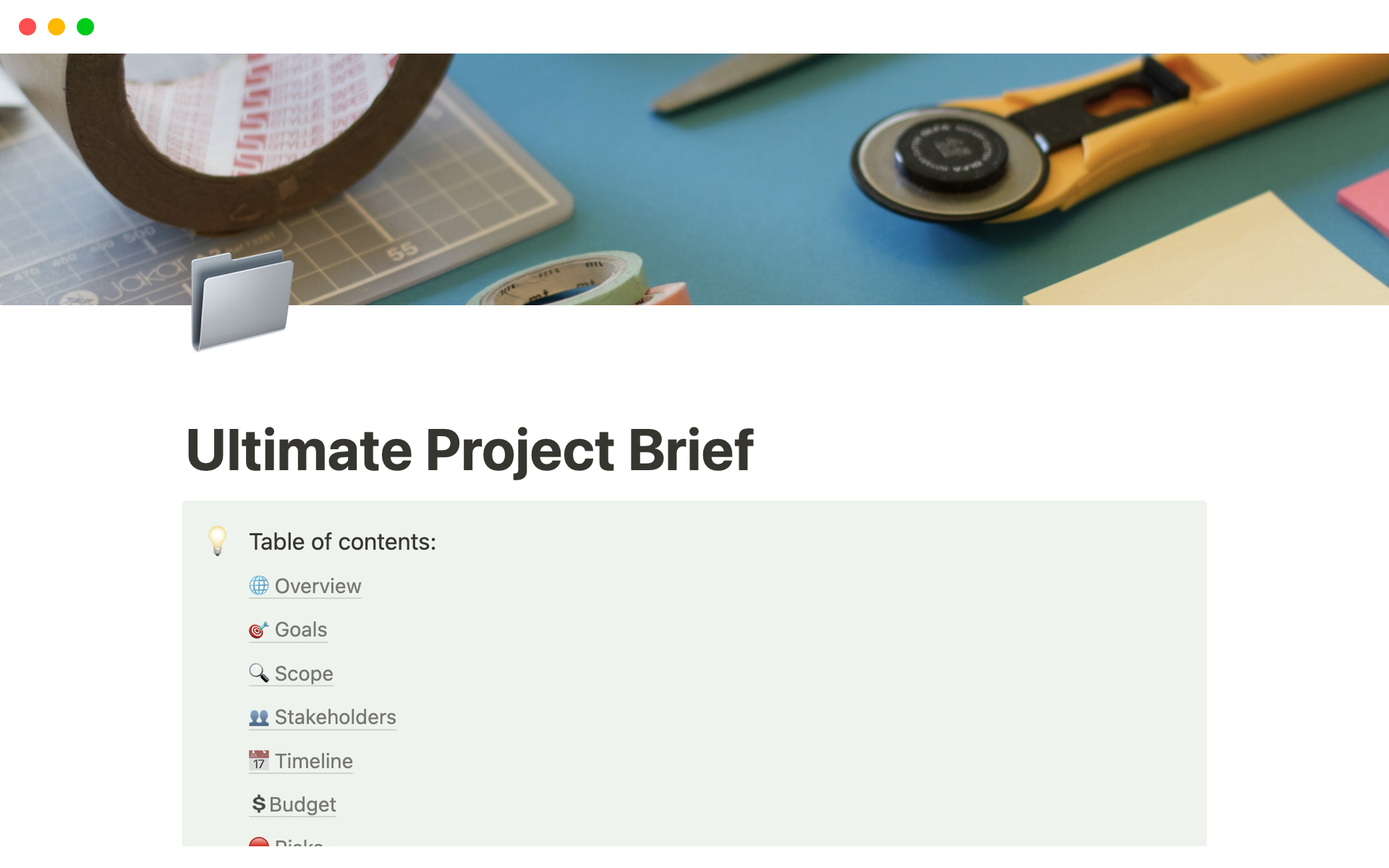

Notion takes so many cues from the Eames’ design philosophy, from building tools that are long-lasting to bringing a bit of playfulness and joy to work. So for Figma’s Config 2024, we teamed up with the Eames Institute to make a little zine entitled Serious play. In case you missed the conference this year, we’ll be sharing a few excerpts here.

In this conversation between Notion’s Shoshana Berger and Eames Institute chief brand and marketing officer Sam Grawe and chief curator Llisa Demetrios (who also happens to be Ray and Charles’ granddaughter) they discuss why play is the prelude to serious ideas, “found learning”, and borscht.

Want to read more like this? Watch this space, we’ll be posting followup articles soon.

Walking into the sun-drenched Eames Institute in Richmond, California, I’m stopped in my tracks. The towering figures of Charles and Ray, wallpapered at the entryway, hold each other’s hand and grin down at me as if today is the best day of their lives.

“Selfie!” I demand of Sam Grawe, a friend from long-lost magazine days who’s now chief brand and marketing officer of the Eames Institute of Infinite Curiosity.

Even before we head into the archives for a short conversation in advance of the day’s tours (they’re offered to the public three times a week), I’m surrounded by the Eameses’ world: vintage toys, one-of-a-kind prototypes, iconic furniture, and crowded sketchbooks bursting with ideas.

This is the trove lovingly preserved by Llisa Demetrios’s mother, Lucia Eames, after Ray’s death in 1988—a collection that offers a rollicking glimpse into the minds of the design world’s most famous pair. As Llisa, now chief curator, guides us into the bowels of the building, I’m buzzing with questions about her grandparents’ approach to play, problem-solving, making, and what modern tool-builders like my team at Notion might learn from it.

Charles and Ray seem to grin wider, as if letting me in on an inside joke. Here’s an abridged version of the interview.

Shoshana Berger: How did Charles and Ray think about solving every day problems at work and in life?

Llisa Demetrios: That was exactly my grandparents’ philosophy. They considered themselves tradesmen, solving problems that came their way or that they noticed in the world around them. And at the core of their approach was an embrace of play and curiosity.

Sam Grawe: There’s a quote about toys being “the preludes to serious ideas.” That’s really the clearest distillation of their thinking. They saw in toys an intentionality, an honesty, a care, a sense of quality—but also an invitation to have fun and explore.

SB: We’re also trying to infuse work with playfulness. Llisa, you mentioned visiting their office as a child and being encouraged to see their prototypes as opportunities to learn.

LD: Absolutely. Ray and Charles would share whatever new movie or project they were working on. They never talked down to us—they shared whatever they were working on with us, whether a three-screen slide show, a short film or a prototype. And they’d meticulously keep track of what each of us grandchildren had seen or experienced, so they could introduce us to something new.

People often ask me, “What’s your earliest memory of spending time with your grandparents?” It’s going out to dinner with them. Charles once asked me, “What’d you think of dinner?” I was eight years old. It was borscht. I said I didn’t like it very much. He said to me, “Well, how would you have done things differently? Do you know what borscht is?” I said I had no idea. I just knew I didn’t like it. He said, “Well, there’s potatoes, onions, butter, beets.” And then we thought of other things you can make with those ingredients. You could have made mashed potatoes. Then we walk a little bit further and he asks, “Why do you think we had borscht tonight? Is it a favorite dish? Is that all that was at the farmer’s market?” It made me just look at the whole situation differently. And I wasn’t criticized, I was empowered.

It was learning by doing, being very hands-on. But you could also put a little twist on that by saying it’s learning by playing. When I visited the Eames office when I was growing up, it was very immersive and they always talked about finding moments of found learning. Less teaching, more found learning. And when you’re playing, that’s found learning, too.

SG: That spirit of play wasn’t just frivolous amusement, though. It was a way for them to understand materials, test ideas, engage with the world around them.

LD: Exactly. When they were working with new materials like plywood or fiberglass, it was an opportunity for Ray, coming from a painting background, and Charles, coming from architecture, to experiment and play together before taking their ideas to the larger office team.